I’m Sticking with You, illustrated by Steve Small and written by Smriti Halls

I’m Sticking with You, illustrated by Steve Small and written by Smriti Halls, is one of the five books on the shortlist for the 2021 Klaus Flugge Prize.

The judges found it really well crafted, particularly in the relationship between the characters, enjoyed the deadpan humour in the illustrations and the book’s pace and movement.

Judge Mat Tobin interviewed Steve about his book.

Mat: I want to start by congratulating you on the collaborative work here with Smriti. You’ve done a brilliant job of playing with the words and interpreting them with humour, movement and a wonderful sense of comedic timing. Were there any challenges in getting that balance between complementing and ironically playing with the text?

Steve: Thanks! Smriti conveys the entire story as a wonderful stream of dialogue from both characters. We get a clear sense of their inner voice throughout and insofar as the twists and turns of feelings and thoughts, each character acts as a reliable narrator of how they see things. It provided an absolutely solid trajectory for the story and allowed me plenty of latitude to observe what else might be happening in the different scenarios. Its plenty of fun to illustrate the dialogue with images that provide a suitable and entertaining backdrop for the story, but when the characters were being so focused on themselves and being hilariously ‘me-me-me’ it also presented tempting opportunities to glimpse other aspects of the situation and see what the context had to add to the story.

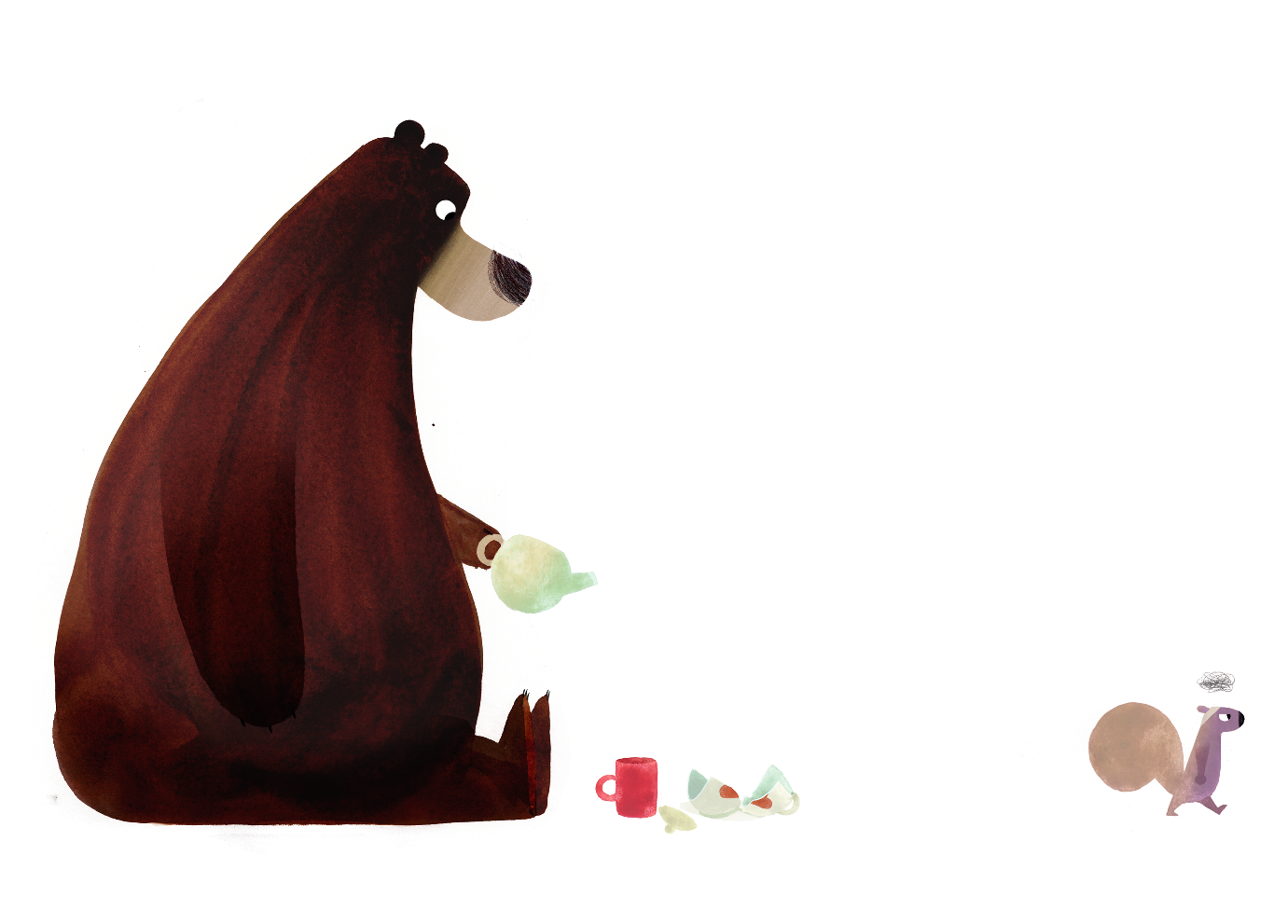

For example, when we read about Bear’s enthusiasm towards Squirrel at the beginning of the book, I wanted to show Bear, large and happy and filling the page. But I also wanted to show Squirrel’s uncertainty when faced with Bear’s rather daunting eagerness. We haven’t heard Squirrel’s side yet in these early pages, and like Bear, we might not immediately spot that Squirrel is having doubts. In this way we might almost empathise with both Squirrel AND Bear when we see both of them unintentionally on different sides of a situation.

Similarly, even though a character might have heartfelt intentions, their actions might not be very successful expressions of them. I’m thinking here of the way Bear’s enthusiasm causes Bear to not notice the effect Bear is having on Squirrel, and just carries on regardless. But equally how Squirrel gets so grumpy that it’s hard to see Bear’s endearing qualities. I enjoy spotting these contrasting opportunities in each scenario. It’s fun with two characters and can get more interesting or amusing (depending on the mood of the moment) when more characters are added, because they’ll all have different timing and personas.

Mat: So much of why the story works so well is because of the hilarious play on the size differences between Squirrel and Bear. I particularly loved the shift in perspective in the igloo to emphasise Bear’s imposing body (and gentle ignorance). Did you have fun playing with these differences and was there a particular spread/idea you felt in which it came together well?

Steve: The size mismatch is a good comedic device for expressing misalignment between characters. Making this book, I established the size relationship fairly early on with an idea for the cover… (excuse the splotches. A brush tried to make a run for it.)

Their size difference made me laugh and I wondered how these two could make their friendship work.

Within the story itself, I wanted to emphasise the consequences of this mismatch on smaller interactions, and see if I could convey subtler ideas with gentle humour, rather than showing too much of the broader slapstick side.

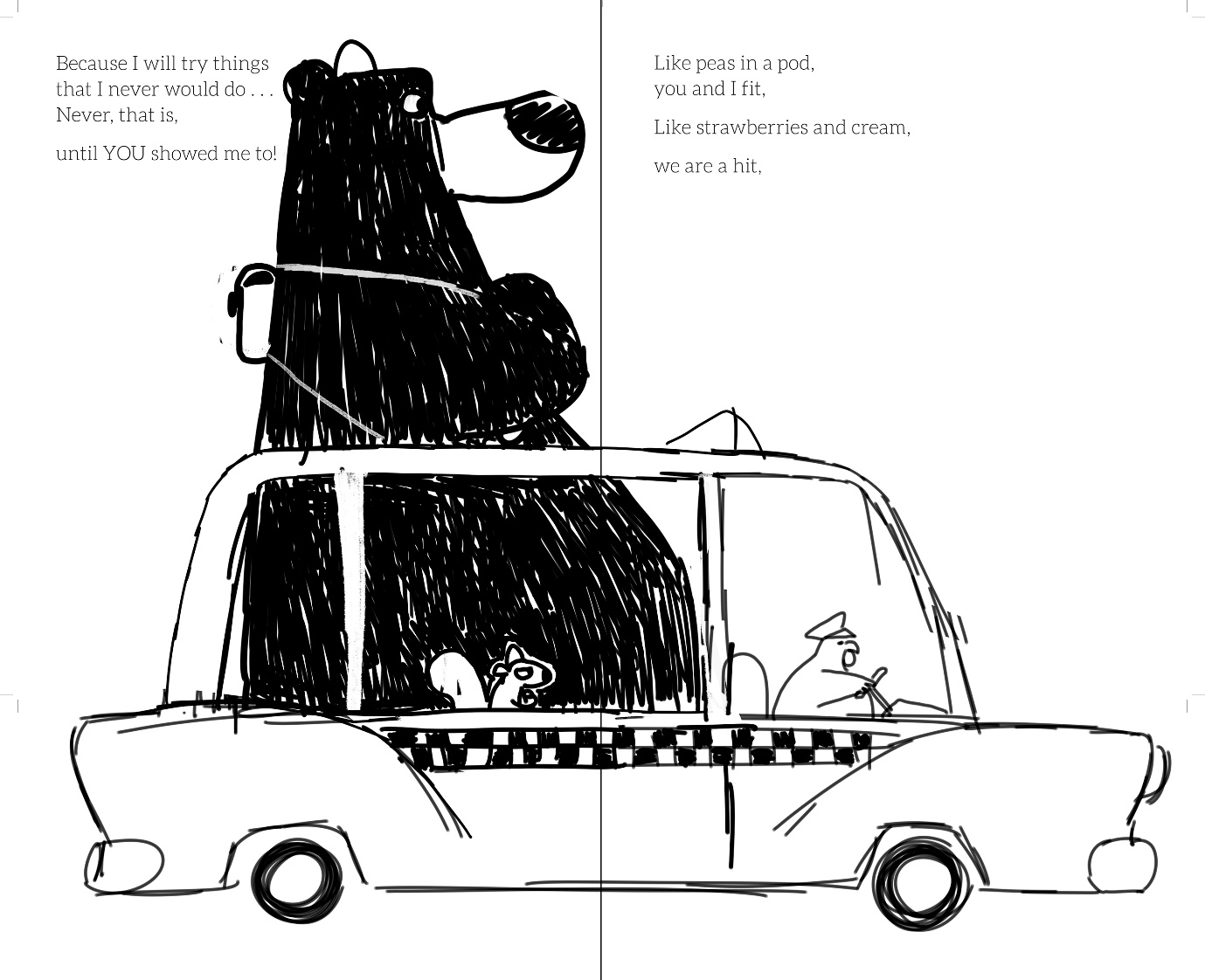

Bear and Squirrel packed into the Taxi is perhaps a good instance of this.

Here, Bear is talking about how great everything is going for them both, and what fun they have together, whereas the truth is that Squirrel had actually been trying to escape at this point in the story, and Bear had jumped in uninvited. I wanted to create an image that showed the amount of fun that Bear was having, but also highlight a real division between Bear and Squirrel. I thought a big yellow taxi driven by a very professional chicken would be a way to do it.

Popping Bear’s head through the skylight seemed to represent what was for Bear, unimpeded progress and a clear view of their perfect future. But it also meant Bear, yet again, couldn’t see Squirrel, in this case, all scrunched up in the corner of the taxi against the window, unnoticed and not in the best of moods.

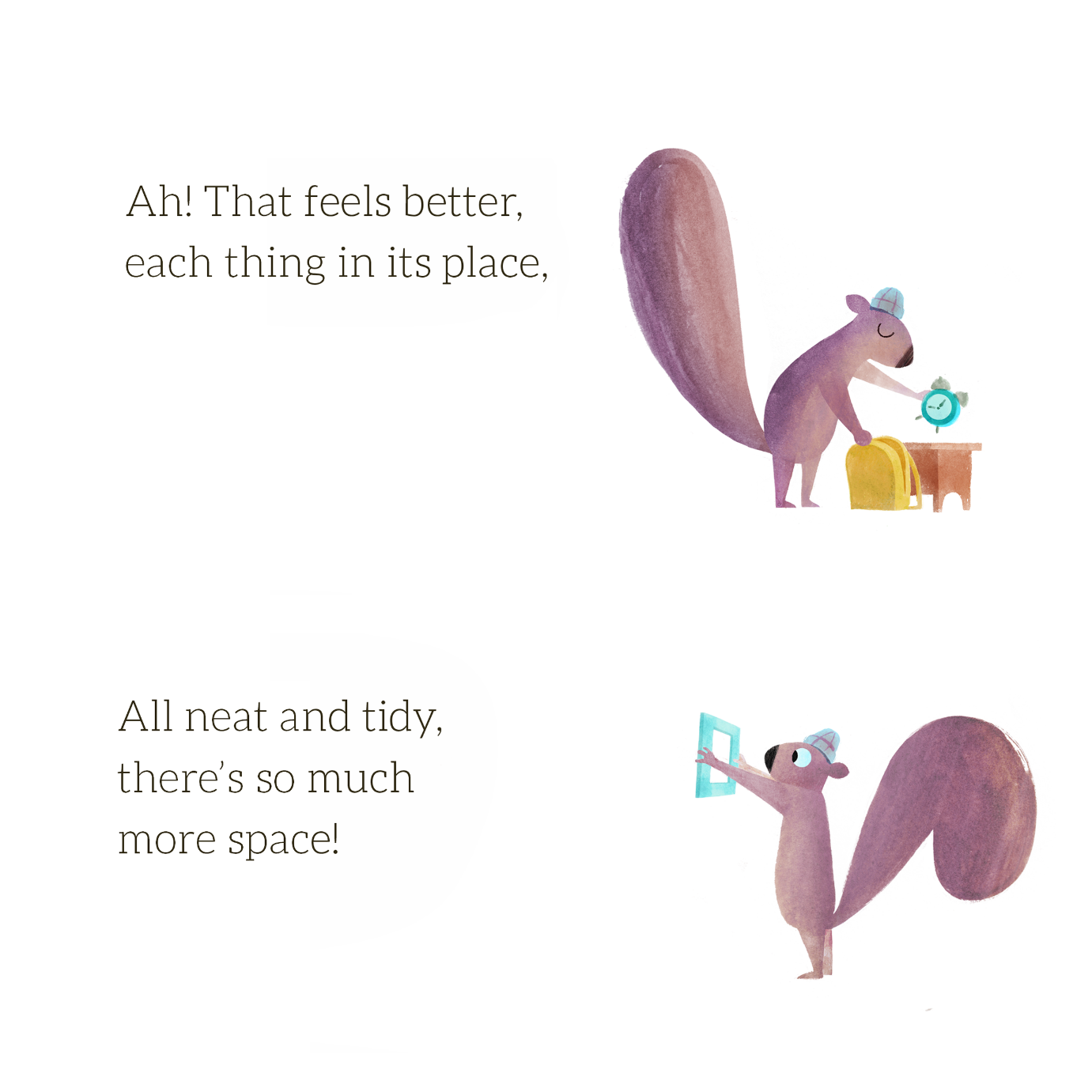

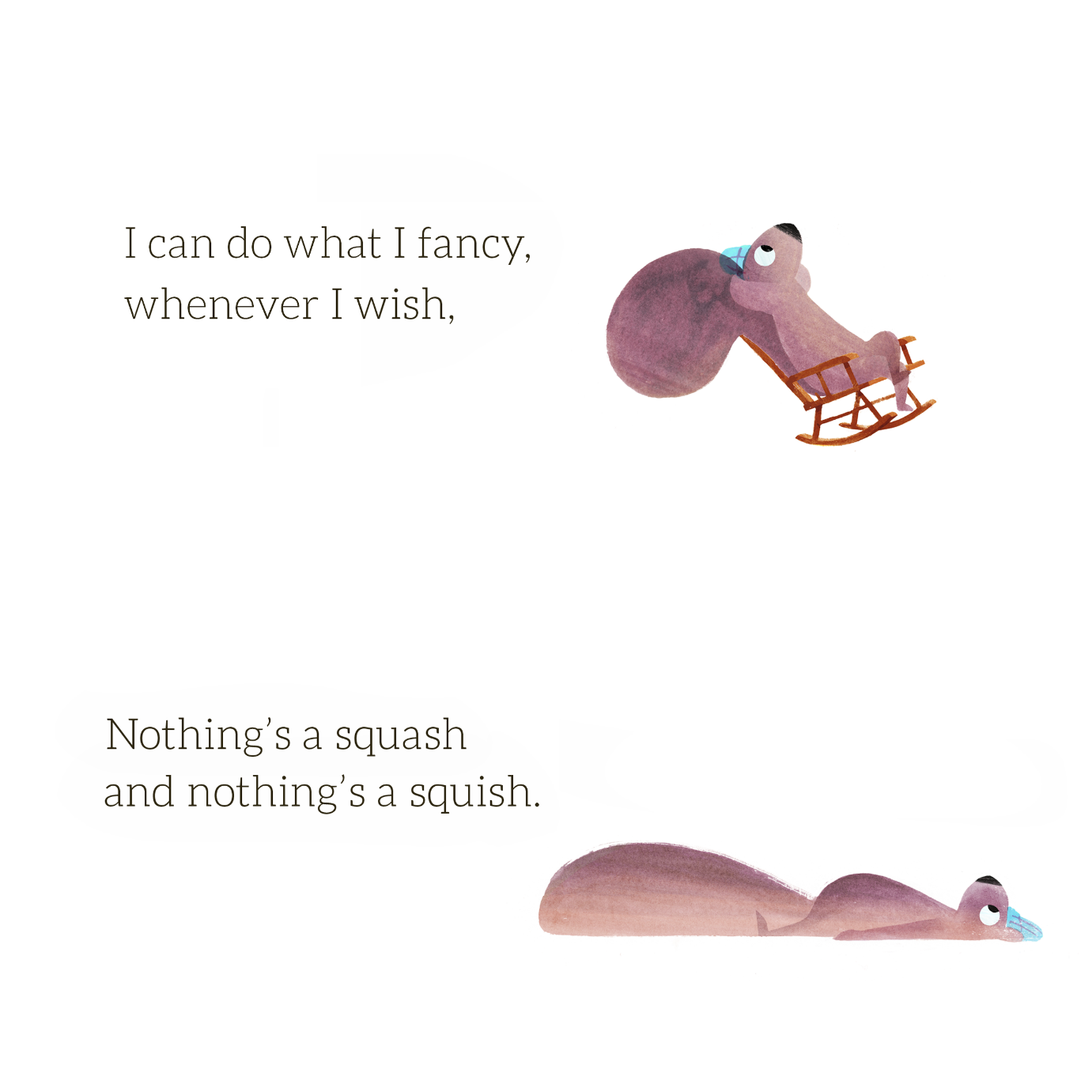

By the time they arrive at the destination, I tried to think of a tight spot devoid of warmth and far away. An igloo seemed to be the right fit, though I ended up not really painting it in much detail. I wanted it to be a feeling of an icy place rather than a realistic igloo, so that it might suggest a feeling of what their relationship had become, as well as being an actual physical location. So when Bear leaves, Squirrel is in a chilly void, trying to make it homely…

…but sadly, much like Squirrel’s emotional state, it is a cold empty space with nothing but token memories offering little real comfort or solace and compels Squirrel to realise just how important really Bear is.

Mat: I know that you have worked in animation as a director, designer and animator. What skill sets did you bring from the industry to support you in making that transition to the picture book format? In what ways are animation and picturebook illustration both similar and different?

Steve: Animation has many tools at its disposal to deliver a story. Movement, music, sound effects, voices, and even the determined length of time that the audience is able to soak up each moment, is thoroughly decided by the storyteller. In many ways, the act of imagination has already happened to such an extent in the making of animation, that little further interpretation is required from the audience. It is a very rich medium and can deliver a story with a great range of expression.

Books without pictures operate with a more slender framework. And even though Picture books are adding a few extra storytelling devices to the pot, such as the appearance of the characters, the mood as suggested by the setting, the humour etc, they are still just snapshots of single moments from often quite intricate stories. And yet amazingly, the images populate our imaginations throughout so many aspects of the story even when there are no images.

I think it is this aspect that I find so intriguing.

As an illustrator, selecting certain events for illustrations allows the reader to have all the fun of leaping from one illustrated moment to the next, and filling in the visual space between one illustration and another in their minds with nothing but the words to prompt them. Its surprisingly interactive in a non- tech way, and allows the reader to personalise the story and add their own perspective and mood to it. Plus, the idea that as a reader, we can linger on each page for as long as we want, and let our attention rove around the page, is interesting to me. There are many spreads in many books that I have grown up with that stick in my memory, and to recall them generates almost as much of a feeling as a memory from real life.

Mat: There is a lot of work that has gone into timing and pace throughout the book. Sometimes we have bold double-page spreads and then a series of smaller images to carry the story along or catch a funny moment. How long did the planning process for the book take and did it go through many changes?

The great thing about all storytelling is that it’s like air and can fill even the tiniest spaces. Sometimes I like to take a more distant view and look at the whole scene. Other times, it’s interesting to select particular incidents from a longer timeline that are weeks or seasons apart.

Conversely, things can happen in the briefest of moments on the smallest of stages, and in storytelling, the examination of an event that is over in a few seconds can be very entertaining to scrutinise over a few images.

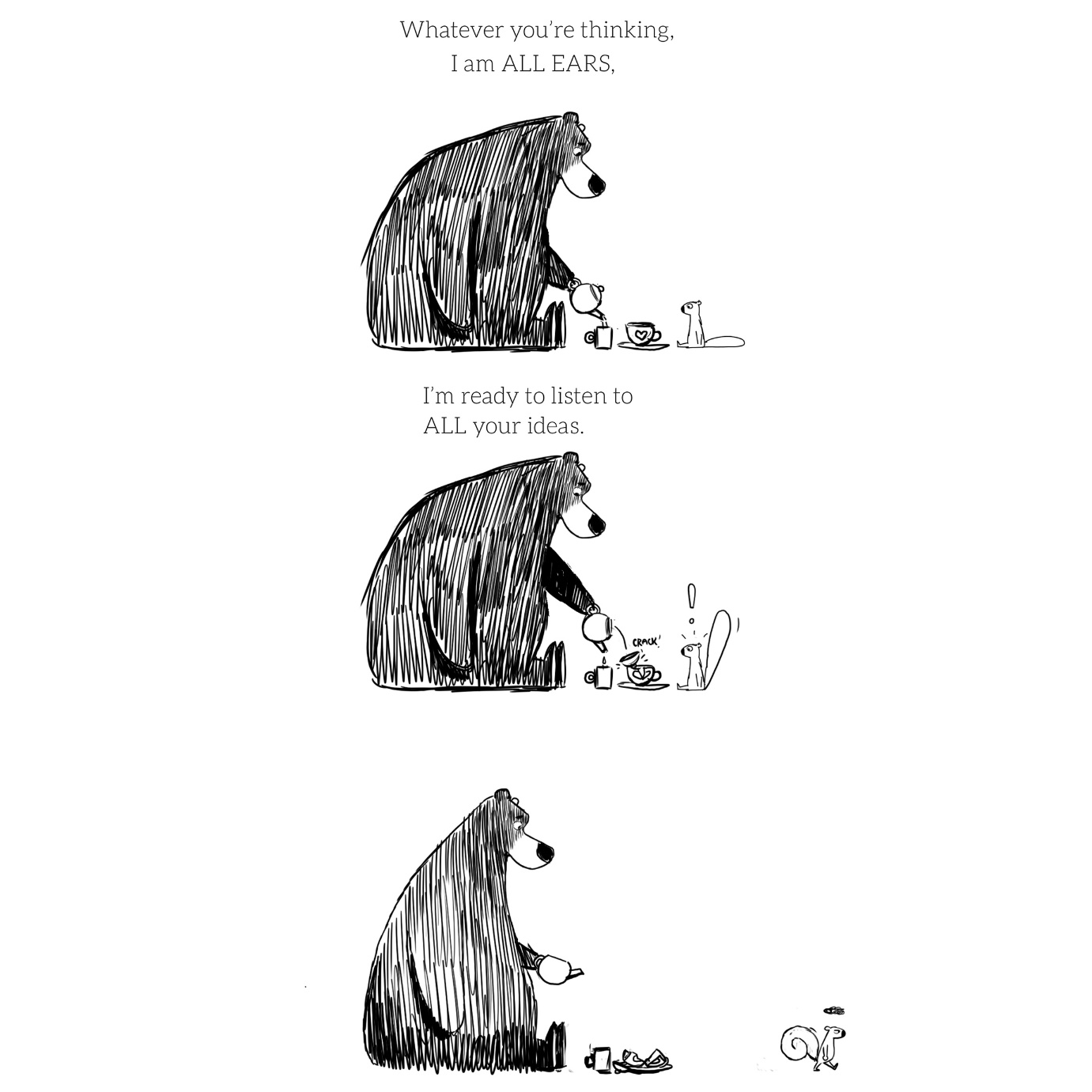

For example in I’m Sticking with You, when Bear pours Squirrel some tea, it’s an act of kindness that instantly transforms into a moment of thoughtlessness when Bear allows the lid to fall off the teapot and break Squirrel’s favourite mug.

It’s not intentional on Bear’s part, but demonstrates how Bear sometimes doesn’t pay enough attention to Squirrel in a meaningful way. This seemed an impactful exchange that reflected their main dilemma, and one that felt right to separate into three illustrations to clearly demonstrate how the dynamic can change in even the smallest of moments.

Mat: Can I be cheeky and ask for a tour of your workspace. It’d be great to see some of the materials that you work with or spaces that are important to you. I know you work a lot on a computer so please feel free to mention specific programmes.

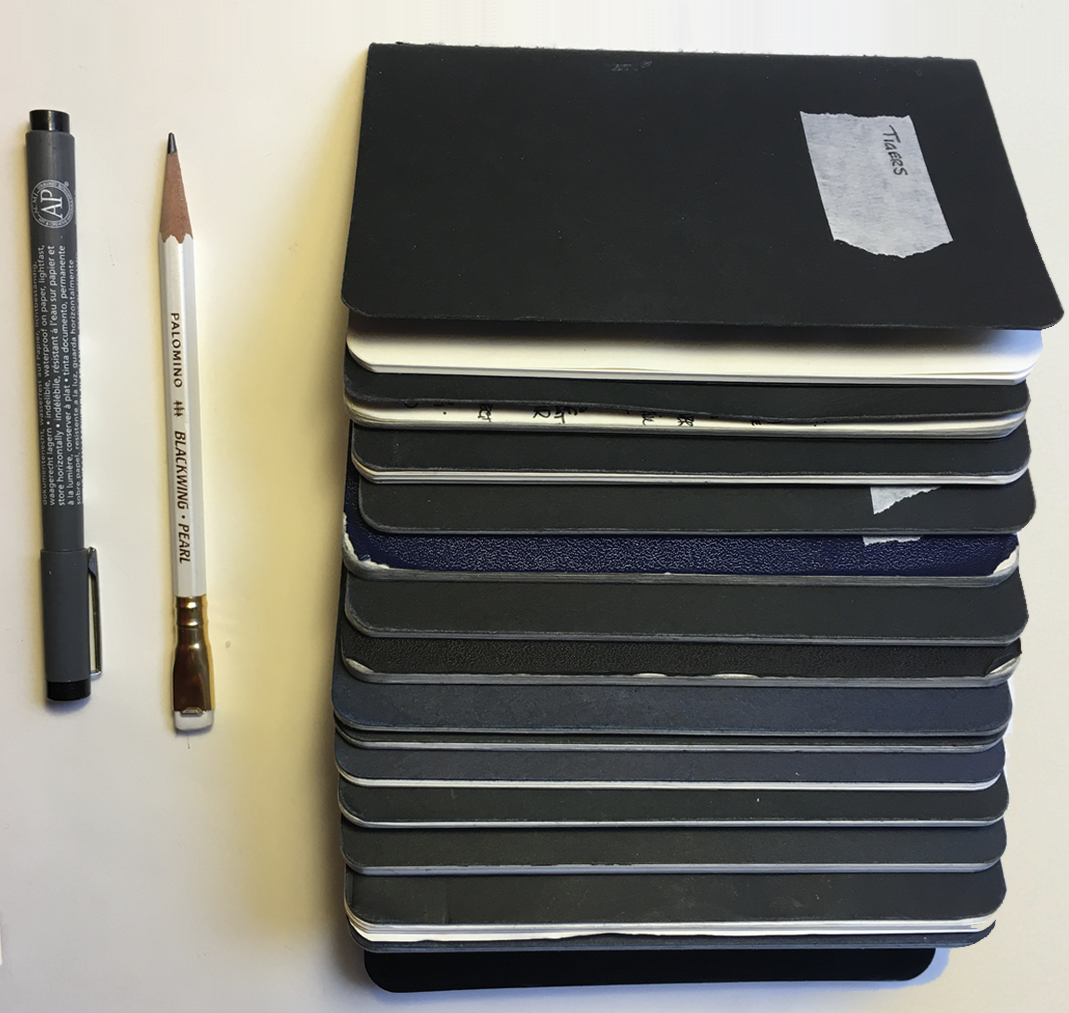

Steve: I do like to work on computer but I would be lost without many traditional materials. I sketch all the time and carry pocket plain Moleskine sketchbooks every. Blackwing pencils for delicate sketches and Staedtler pigment liners for those bolder doodles.

When it comes to artworking, I like to have reliable brushes for control and unreliable brushes for surprises. No brush gets thrown away. I often use my favourite type of animation paper to make finished drawings on, which has just the right non-absorbency and translucency to be able to make accurate sketches from guide sketches underneath. Speaking of translucency, the best piece of technology in any illustrator’s toolkit surely has to be the new LED lightpads that are available now. Slender, very bright and very portable. Amazing. I spent so many years working on large animation light desks trying to figure out how to get the bulb closer to the plastic surface without overheating.

Mat: Can you talk a little about working with Simon & Schuster, the editor and the designer? How did this experience shape and guide your work? With whom did the choice of the book’s shape and format lie? The portrait format meant that there was room to focus on character and celebrate bear’s ‘size’ and I think it was super as was the choice to us a lot of white space.

Steve: Jane Buckley, the Children’s Book Art Director from Simon and Schuster got in touch with me a while ago and asked if I had ever thought about doing Picture books. I have always loved them, and the idea of making them seemed to be forever out of reach largely because animation is so time- consuming to produce. (Despite amazing software and tools continually arriving on the market to make animation more achievable, it’s still very labour intensive if you want to make something interesting.)

But I thought it was the right time to try it.

Jane introduced me to Helen Mackenzie Smith and we all had a fun afternoon discussing sketches and past work. A week later, Helen sent some scripts for me to read. As soon as I read Smriti’s script, I knew immediately that this would be the first Picture book for me.

I was a complete novice to books and quickly learnt that there are many nuances to every aspect of making picture books. To their immense credit, Helen and Jane allowed me free rein to try out anything that popped into my head, and then set to work with me to make sure that we could actually make the ideas happen in print.

Count yourself lucky if you ever get to work with an Editor and Art Director half as talented as Helen and Jane. I’ve have always secretly suspected that the mark of a true expert in any field is most evident in the lightness of touch with which every step is steered invisibly and impeccably in the right direction. This describes Helen and Jane to a tee.

As I started working on roughs, I quickly realised that I wanted as tall a book as possible, but one that could fit into a shelf.

I love rich images and the ability for Picture books to create worlds and set their stories against backdrops entirely personal to the story and the characters is for me, an essential pleasure of visual storytelling. And yet it my own work, I like to try and distil ideas and images to their simplest form. It still allows for layers of interaction and emotion in the illustrations but keeps it simple and easy to access.

Still, every now and then, when you’ve set up a rhythm of simplicity, there’s nothing better than to place a rich and densely colourful spread in amongst it all. In I’m Sticking with You, these were the night-time spreads near the igloo. I am a fan of night-time scenes in picture books and when you’ve spent a lot of time in the bright world against white space, a spread full of night is a fun surprise.

Mat: I know we have more to look forward to from you on the picture book front with The Duck Who Didn’t Like Water and this time you’re working on your own. Can you tell us a little about the story and the new challenges/benefits working independently has brought with it?

Steve: When I first started writing the story, I thought that once it was finished, I would already have it in my mind and would only have to illustrate the ideas on the page. But it worked out a little differently.

When you work with someone else’s idea or story, a lot of your job is to treat it like a map to buried treasure. You go off in search of all the hidden and buried treats that have been carefully placed there by the writer and discover them much like the first-time reader will. Once you have safely navigated all the hidden caves in the story, it’s your job to become the official guide for future visitors to walk through and experience this treasure trove to its fullest extent, without disturbing the delicate and precious ecosystem in which it is set.

The difference between working on someone else’s story, and working on your own, is that as the writer, you are already very familiar with most of the treasure. So when you take off your writer’s hat and put on the illustrator’s hat, the treasure is not particularly buried. You might think therefore that you already know it. But it turns out that first experience of encountering a story with a fresh pair of eyes, the way a reader will later, is really useful. There are some ideas that felt great when written and even the image you conjured up while writing might have been interesting too. But at least with me, it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s going to work on the page with the text in the space you have available. This is where you need to get thinking again, and sometimes it’s harder to re-see it and re-imagine many parts of an idea that already existed in your writerly brain.

For these reasons, I realised that the creative act of making, changing, discarding and re-making things continues right through writing AND illustrating right up until the last proofing run.

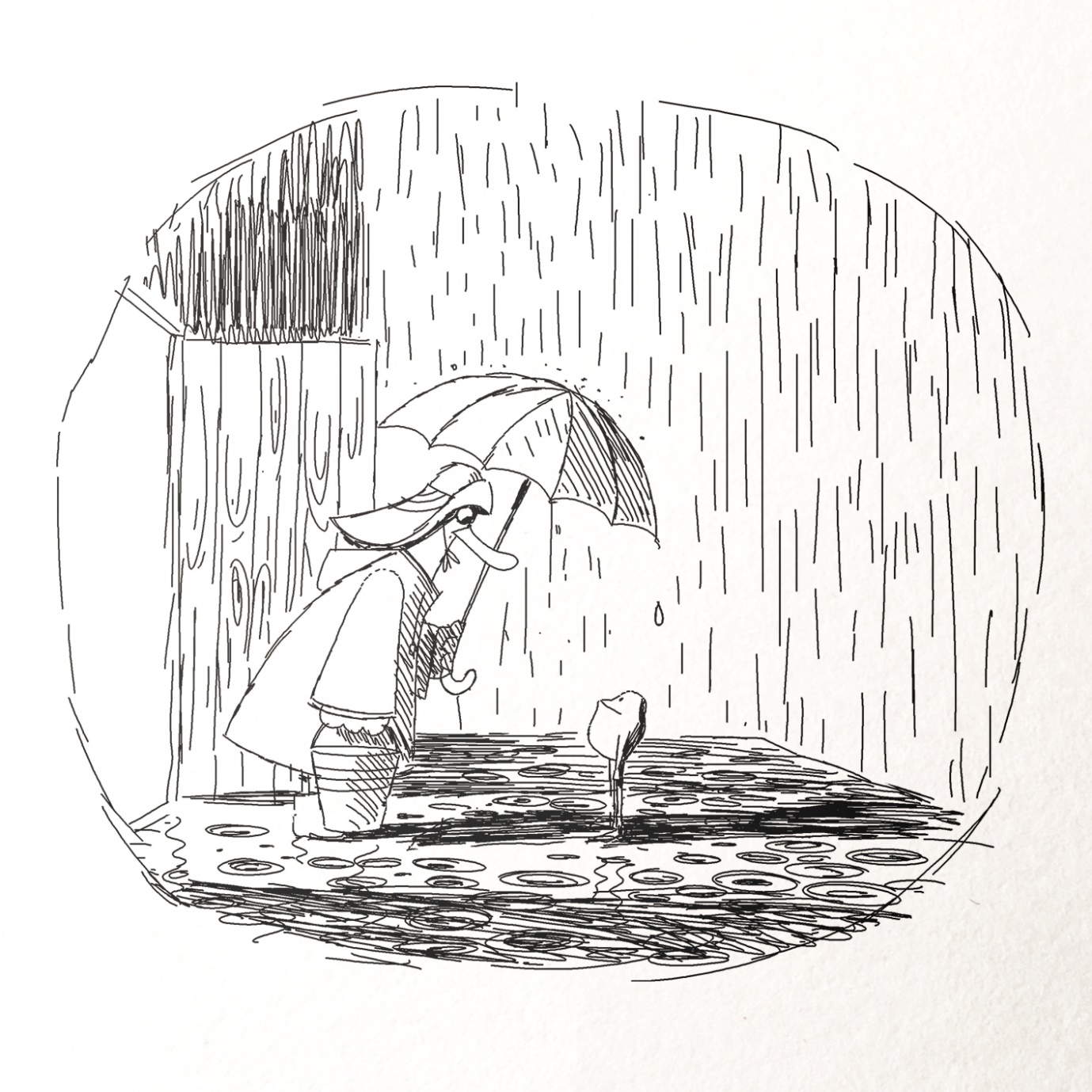

My first solo book where I discovered this was The Duck Who Didn’t Like Water. It is about a Duck who doesn’t like water who, one night, meets a Frog who does. It is a story about two future friends who discover that you don’t have to see eye to eye about everything to get along. It is also a reflection upon the idea of home.

There is a lot of white space in this book too, The three most colourful spreads illustrate the two big storms, one where Duck meets Frog and the other where Duck has to go and find Frog again. Both these spreads bleed off the page and, I hoped, helped convey how wild and encompassing they felt to Duck. It is really Duck’s story, but Frog too is on a journey.

Mat: Were there any picture book illustrators that had an impact on you when you were growing up or who you admired?

Steve: I had a Disney compendium of the Golden Book Stories and two Dean’s Treasury books of Fairy Stories and Nursery Rhymes. Gustav Tenngren, Mary Blair and Janet and Anne Grahame Johnston were my early favourites.

Mat: Are there are any contemporary artists/illustrators whose work you admire now and who you think everyone should encounter?

Steve: This could be a very long list. I admire many Graphic Novel artists working today, Cristophe Blain, Joanne Sfar, Manu Larcenet, Emmaunuelle Guibert, Marjane Satrapi and Rutu Modan to name a few, are such fine visual storytellers, able to convey complex themes with such artistry.

The cross-over that artists make from animation into illustration can be fascinating too. Talents such as Michael Dudok De Wit, Manshen Lo and Marc Craste are great artists whose work creates fascinating imagery and stories in animation or illustration.

Animators working in Independent animated films have opportunities to make stand alone and extraordinary artistic narratives and explore unusual territory. Koji Yamamura, Atsushi Wada and Igor Kovalyov are terrific short story tellers.

Mat: Thank you so much for answering these questions, Steve.

I’m Sticking with You is published by Simon and Schuster, 978-1471182815, £6.99 pbk.

The Klaus Flugge Prize is funded personally by Klaus Flugge and run independently of Andersen Press.

Website maintenance & Copyright © 2023 Andersen Press. All Rights Reserved. Privacy & Cookie Policy.