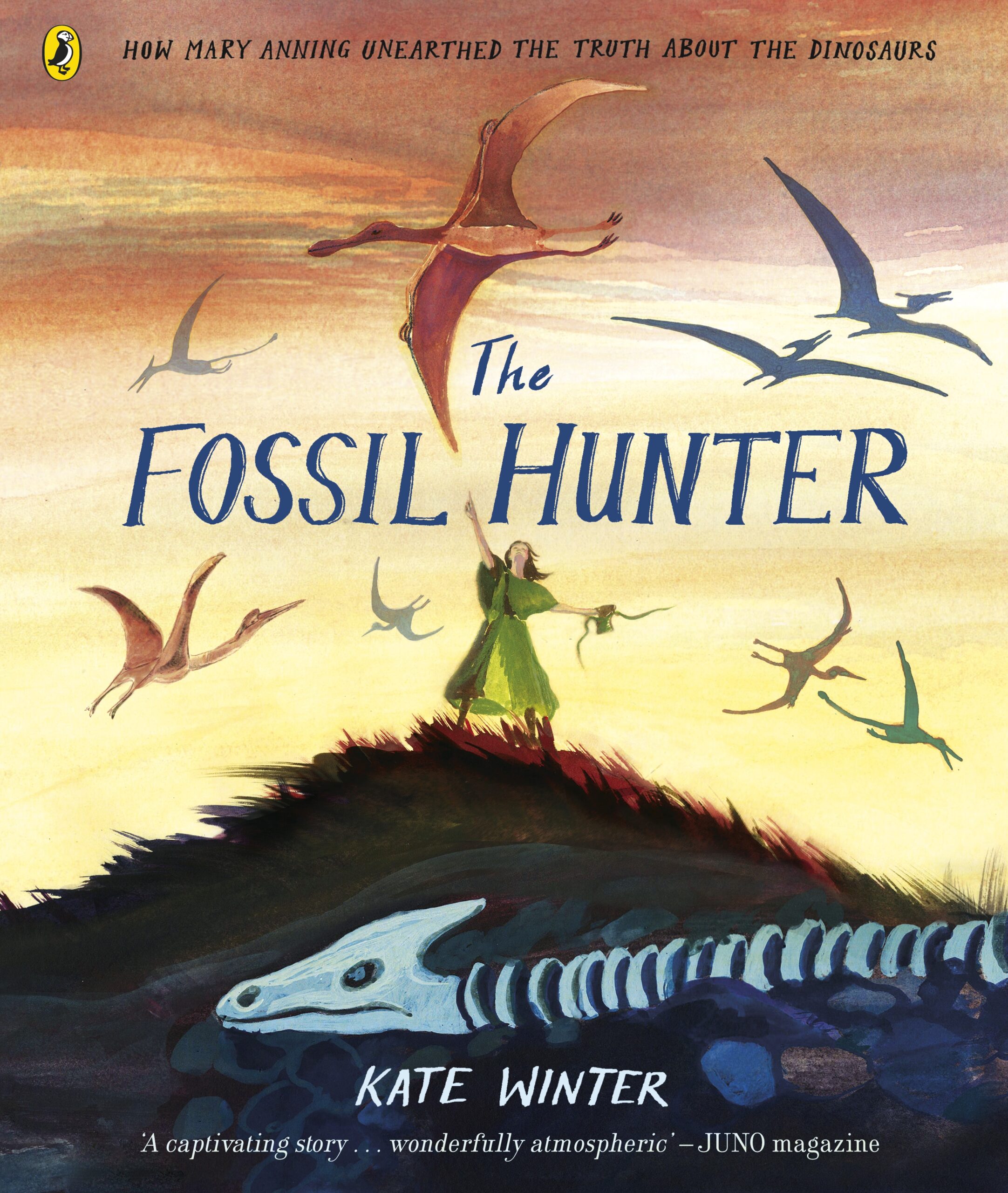

The Fossil Hunter, by Kate Winter

The Fossil Hunter by Kate Winter is one of the six books on the shortlist for the 2024 Klaus Flugge Prize.

Through atmospheric full-page illustrations and detailed vignettes, Kate Winter tells the story of Mary Anning, whose 19th century work discovering fossils in the cliffs of the Jurassic Coast paved the way for modern palaeontology. A beautiful book, said the judges, who admired its sense of freshness, the artist’s observational skill and the strong sense of location.

Former Klaus Flugge Prize judge, Senior Lecturer in Education: Primary English and Children's Literature, Mat Tobin interviewed Kate about her book.

Kate, The Fossil Hunter is a fusion of illustration, story, and non-fiction. Can you share with us a little on how you balanced these elements and what inspired this approach?

During my time studying my MA in children’s book illustration at Cambridge School of Art I developed a story about the cave paintings at Lascaux. I had purely worked this into a narrative, almost a poem that invited the reader to travel back in time mostly through the visuals with large all absorbing double page illustrations. The simple text and questions hinted at what might be going on in the cave paintings and why our ancestors might have painted them. When Lara Hancock and Anna Barnes Robinson saw this they invited me in to discuss other themes they felt might fit with my aesthetic. I worked with Penguin to build Mary Anning’s story into something similar but with a richer text, more factual elements and many more pages. We developed a wider story about the history of the world and a story within that about 19th century society and Mary’s significant role in challenging that society.

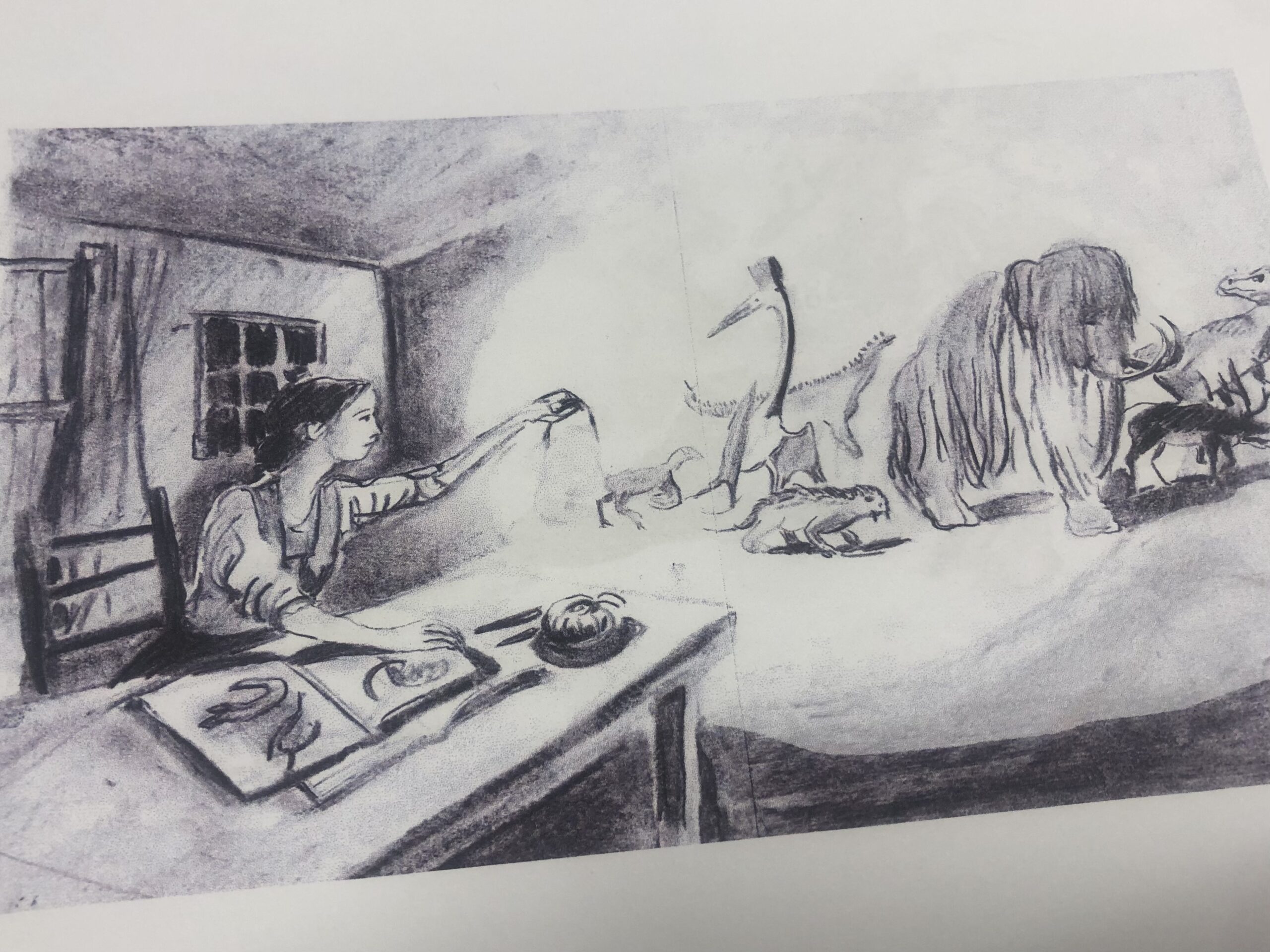

I think history can be brought to life through characters, dialogue and illustration and it felt quite natural to approach the story of Mary Anning with a strong narrative and presence of character. I wanted to write in a way that would engage the reader and pull them into Mary’s world. I wanted the reader to hear Mary’s voice and see her ideas and imagination, so they could understand her motivation and the passion she had for the work she did. The illustrations were integral to that, moving between factual spaces of the 19th century to imagined prehistoric scenes.

It's hard to get that balance right between the information and facts and the all-absorbing story we want to tell. It’s important to get this right so the more factual bits don’t break the magic of the story-telling. The factual elements back the story up and add extra context to further entice the reader back in. It is easiest for me to find the narrative curve of the story and the spaces for the natural pauses when I explore the story aloud, using oral storytelling as a way to feel the flow. Performing or reading the story aloud is an important stage of writing it for me.

Can you share your journey into illustration, particularly your transition from stop-frame animation and other fields? How have these experiences influenced your work?

Prior to writing and illustrating books I worked in film, directing stop frame animation for music videos and commercials. I also made experimental short films. There are lots of connections between that and what I do now. I tend to think of stories like a film playing through my mind. The pacing, the build, the dramatic moments, the reveals, the calmer moments - these moments in films can also be created in books. In film there is a fixed timeline that everyone will experience as the same while in books the time is variable and you never have full control of how long someone stays on a page but you are able to have some control. It is possible to hold the viewers’ attention and conduct their movement from page to page with the images, the words and what you are saying; there is a lot that can be done to suggest the rhythm and pace of a book. I feel very conscious of that, and I think this comes from my film background.

My past life as an animator is also ever present when I’m drawing characters. As illustrators we need to embody characters in our minds eye, to feel their posture or expression; to imagine we are them. It’s very similar when animating, you need to feel the movement in your own body or in your mind. I am sure puppeteers experience the same sensation; visualising a movement to make it a reality on the page or in character. Prior to animation I studied fine art at the Slade and specialised in sculpture but I was always making films and my work revolved around narratives. Drawing has always been my passion and my preferred method for developing and communicating my ideas.

I imagine that a significant amount of research went on in preparation for this book. From Mary Anning’s own life to dinosaurs and clothing/aesthetics of the period in which she lived. Can you share with us some of the joys and challenges of this process?

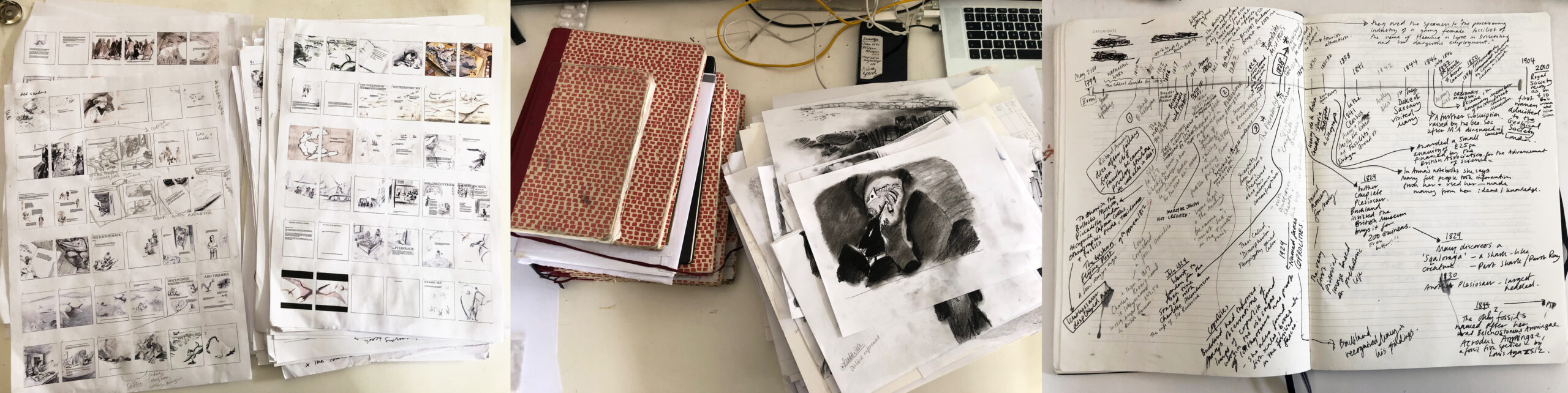

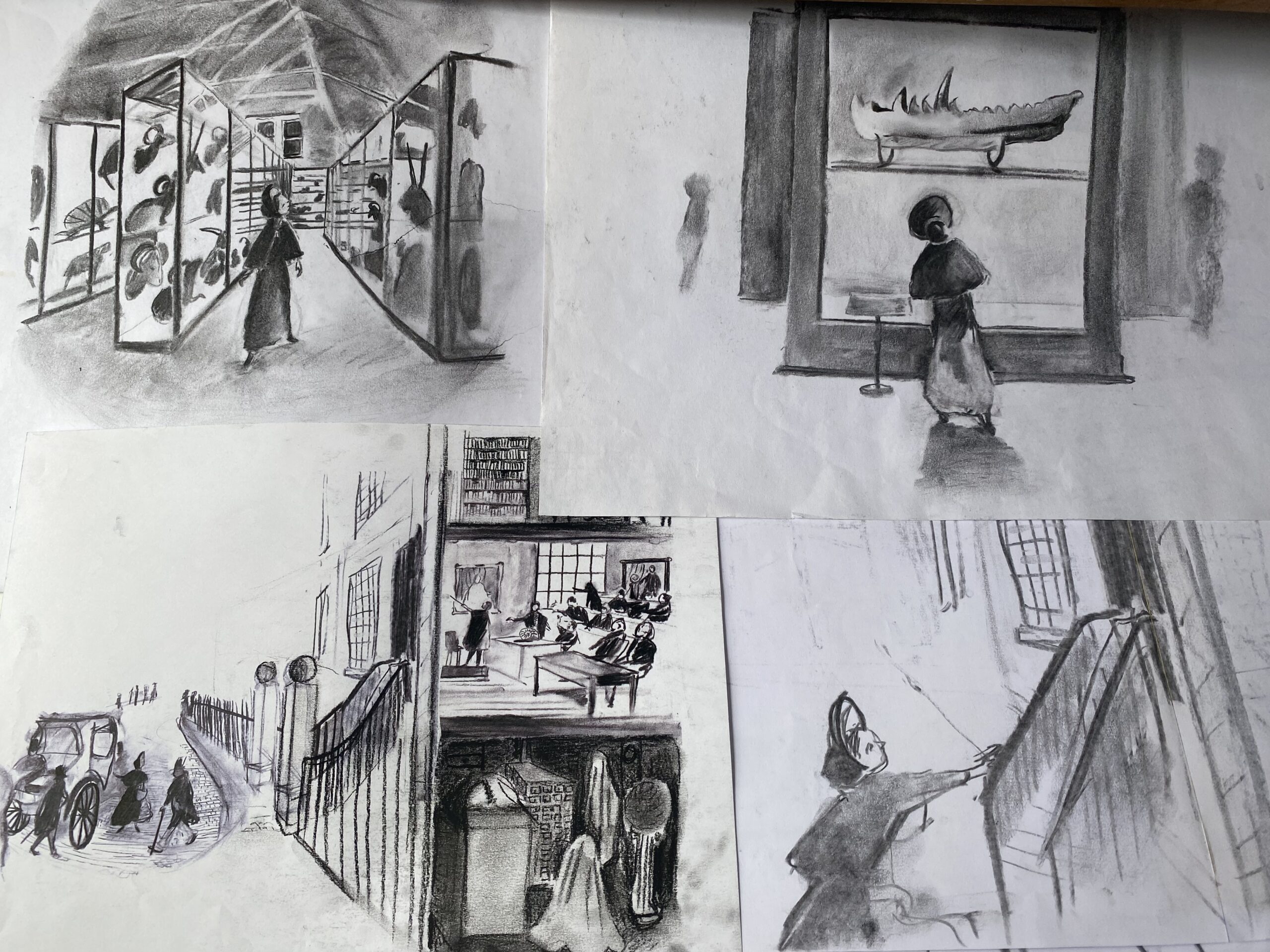

There was a lot of research that went into The Fossil Hunter. Firstly, learning the ins and outs of Mary’s life and all she encountered. Then, as you say the marine reptiles and their prehistoric time-period. This research was done by reading about Mary. Books by Tom Sharp and Patricia Pearce and the Oxford university museum of natural history were excellent sources of information including letters between Mary and her contemporaries. I also got to know Mary by drawing her and her life repeatedly, trying out different ways to communicate the depth of history around her and the depth of her imagination. Learning about her through drawing and developing the story through images as well as words.

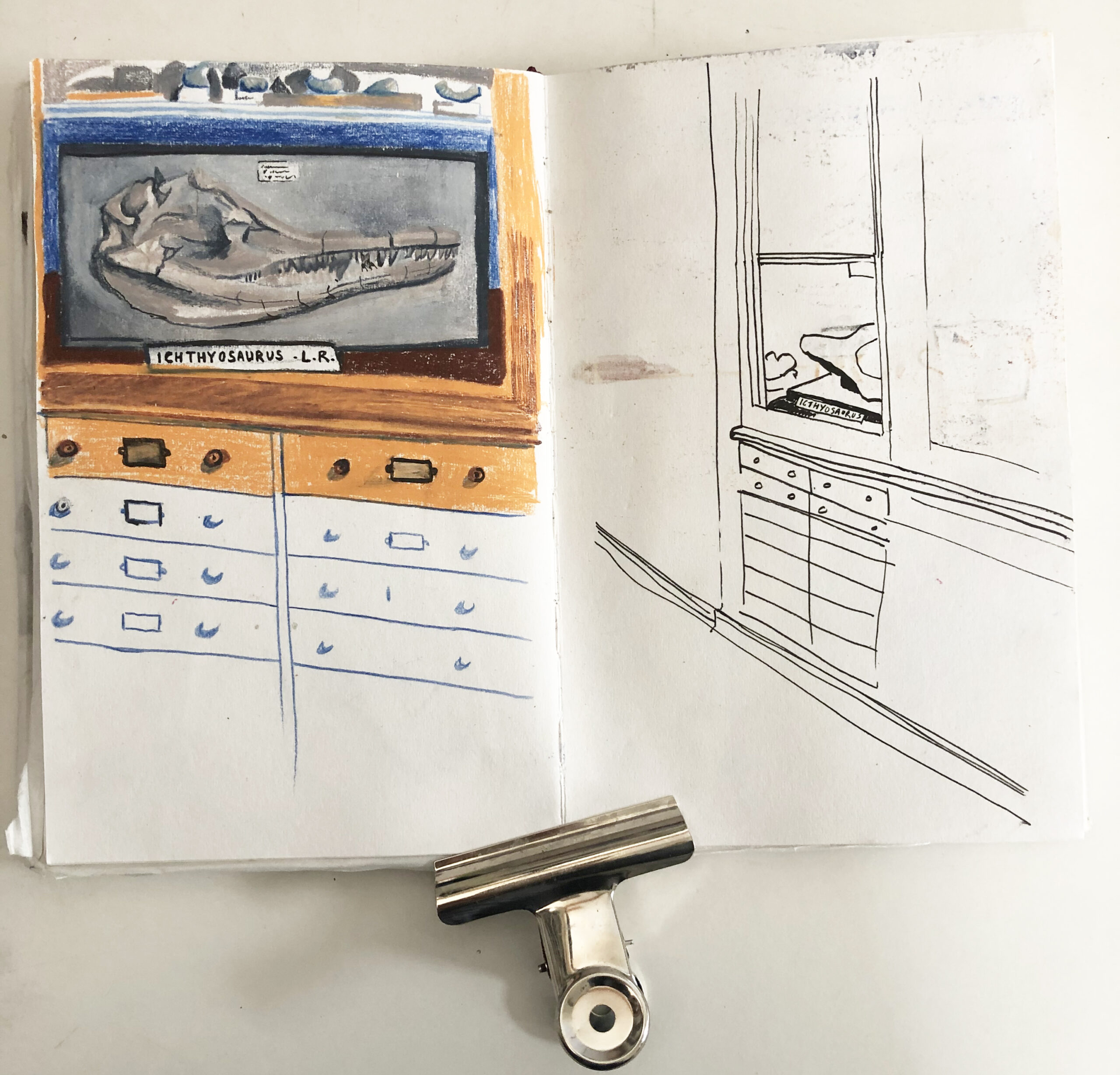

Luckily where I live in Cambridge, we have the Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences who have a wealth of fossils, some of Mary’s finds and finds of her contemporaries. The Natural History Museum in London also holds some of Mary’s fossils. I worked with researchers at the NHM who fact checked my writing about prehistory and made sure I didn’t draw ammonites swimming upside down! Lyme Regis have a brilliant museum with a lot of information about Mary, palaeontology, Dorset and the 19th century. It’s worth a visit for anyone interested in this area.

I spent time drawing in all these places, particularly Lyme where I felt I could imagine Mary as a person and visualise the life she led. The fact I could walk on the same beach she walked on, try my hand collecting fossils and draw the places where she would have been, was so important to me. This was my way of getting to know Mary and who she was. I read a lot of books and pieced together the timeline of her life, focusing on some of the key moments and discoveries. The highlight for me was reading Mary’s own words in letters or journal entries. These helped her become a living being.

How was your collaboration with the editors and designer for this book? Can you share how their input influenced the final illustrations and layout?

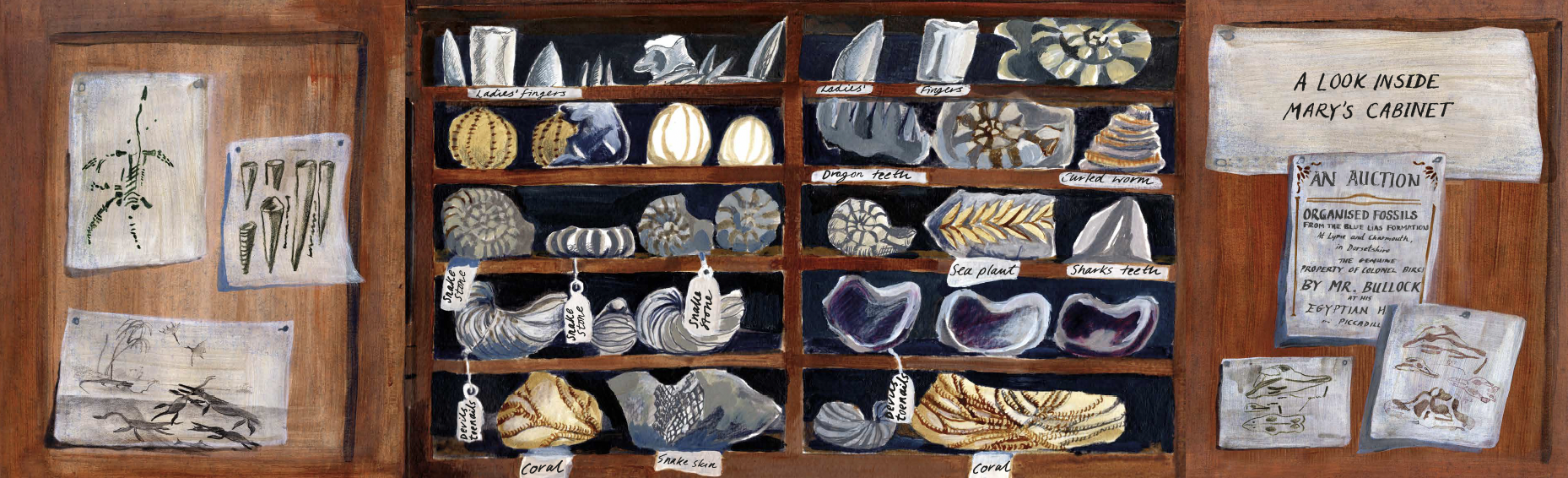

I have a brilliant team at Penguin who were hugely influential in the way the whole book works. I feel lucky to have a team that supports my process and ideas and who also bring great ideas and excellent design to the table. The gatefolds were a good example of this where my idea of the opening cupboard became an option for other possibilities in the book. The whole process was very fluid and there was so much room for creativity and my painterly approach to the artwork. I feel very grateful for that and their willingness to trust me to deliver this book. The book took quite a while to make; almost 2 years and was made during lockdown when we all had many extra things going on including juggling childcare and teaching, which is my other passion. I went through two editors! Lara Hancock and then back to Anna Barnes Robinson who I am working with on book two. Their guidance and encouragement was such a guiding light during those lonely days of ploughing through a thick 80 page book!

I loved how much the whole book tells your story and how certain design elements made the reading experience interactive such as gatefolds. Can you discuss your approach the book’s peritextual and interactive elements and how you wanted them to play a crucial role in the storytelling? Are there any particular aspects you're especially proud of?

The gatefolds are a key part of this book. For me they represent Mary’s imagination. By opening to reveal the prehistoric past inside the gatefolds we feel like we are dipping into her mind to see what she was thinking. I think this is my attempt to deepen the involvement of the reader somehow. It’s like we are peeling back the layers and going inside, down, deeper and closer to the story.

The cabinet gatefold for me is slightly different, rather than connecting to Mary’s imagination or taking us way back to prehistory, I hope the viewer feels somehow transported to the physical world Mary inhabits. I hope it serves the purpose to invite the viewer to step into Mary’s shoes and be Mary: to open her actual cupboard of fossils. In both these examples my intention is to bring the reader deeper into Mary’s world and mind.

Other interactive elements are slightly more subtle. I think posing a question in the book: “have you ever found something mysterious” has a way of drawing the reader in and hopefully engaging them in a thinking state; finding their own connections or feelings of familiarity. I hope it adds a level of identification for the reader; if they know the feeling of being curious and not-knowing then they too will understand Mary and her quest to further our understanding of the world. I am playing with more questions in my latest book.

Other visuals that merge time periods, for instance Mary in the 19th century standing above the ground with visible layers of 250 million years of history stretching beneath her are in some way interactive. I hope they invite the viewer to connect two periods in time; from the physical relative now-ness of the 19th century to the concept of the past and “deep history”. It’s a kind of time travel that the reader needs to go on.

I am continuing to explore these devices in my future books. I’m very interested in how we attempt and manage to immerse readers in the stories or worlds we are creating in picture books. This is for me the most exciting part of the what I do - I aim to make an immersive, almost theatrical experience and the process of finding those ways into stories is what makes me want to create books.

The whole presentation of The Fossil Hunter is so well crafted and something that I felt worked incredibly well was both the pacing of the narrative, largely controlled by the placement and size of the spreads. Were there any significant challenges you faced while working with pacing and positioning of content? How did you overcome them?

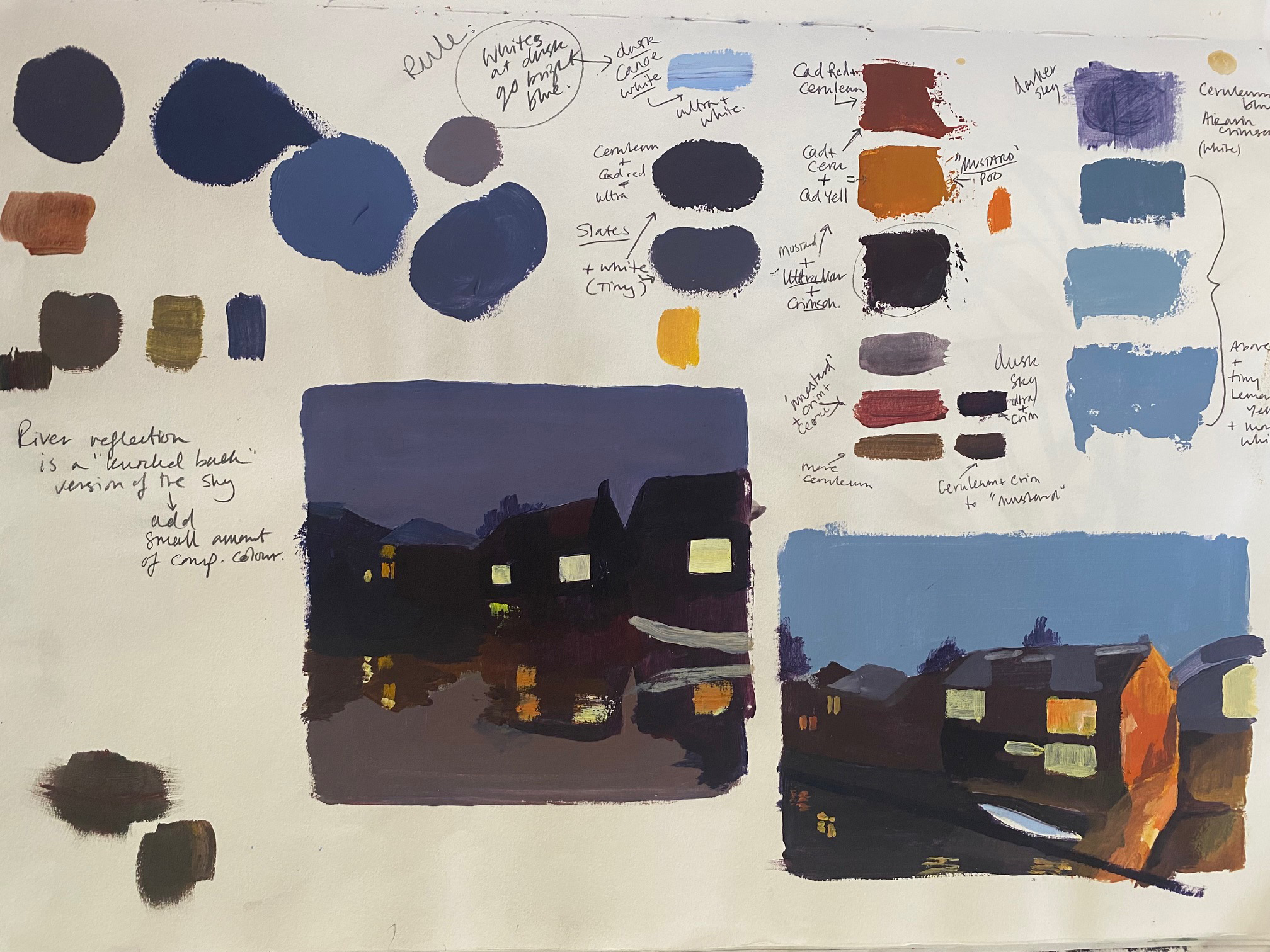

I worked closely on the structure of the story with my designer and editor using charcoal roughs that I could chop up and rearrange in photoshop if I needed to. I worked with my designer in a shared InDesign file so we could tweak things again and again. It was very fluid, and we found a good rhythm. It reminded me of the work-flow for animation where me and my team needed to place-hold certain aspects of an edit with a still visual or animatic before finessing the final work. You get quite used to the ebb and flow of a working relationship and when it works well its brilliant. I am very lucky to work with Monica Whelan who is a fantastic designer and has been so easy to work with.

The whole process of making a book is so interesting. In some ways as an illustrator and writer you are on your own a lot hunched over a desk channelling your thoughts, but the wider picture is of a whole team working together, beavering away at various elements, but all tuning into the same wavelength and vision. As someone who needs freedom but also boundaries and social connection as well as solitude, I feel like I am in the right job finally!

You mentioned your love for still-life drawing. How is this passion reflected in The Fossil Hunter, and what techniques do you use to bring still-life elements to life?

I am a big fan of observational drawing. It’s my meditation, a way to research and explore ideas and practice drawings skills. I have always drawn and love to paint but the MA in children’s books that I graduated from in 2019 at Cambridge School of Art was the driving force to make observational drawing central to my practice.

At the time I was looking for a way to leave the commercial world of animation and focus on my own ideas, but I felt lost and unsure of what I wanted to make work about. The MA helped me focus on what subject areas interested me. It took a long time to notice that all those film documentaries I had planned and not made were waiting for me to realise they could be put in books! Once this penny dropped, I started to explore the idea of the prehistoric caves at Lascaux and how I might make an enticing story around this theme. Luckily Penguin saw my interest in the past and prehistory and asked me to work on a book about Mary Anning. It was the most perfect invitation!

The Fossil Hunter deals with real historical figures and events. How did you ensure historical accuracy in your illustrations, and what was your approach to blending fact with creative storytelling?

This book did need a certain amount of historical accuracy. Luckily there are wonderful photographic and image references that show what England looked like in the 19th century. Lyme Regis museum was a good starting point and Lyme Regis itself has some buildings and features that remain the same to this day. The cliffs on the beaches are still the same cliffs that Mary looked up to. So, I was lucky that I could visit and get some sense of Mary’s time in history. I also watched some good telly and films that showed historical dress, horses and carts, boats etc. Written descriptions can also be so helpful in visualising a place and time. There were many descriptions of a 19th century busy London or the state of the roads that made long distance travel hard, the beach frontage, and of course descriptions of how Mary and the Anning family lived were gathered from reliable sources.

I didn’t watch the Kate Winslet film Ammonite because I didn’t want to be too strongly influenced by another person’s vision and interpretation. It was important for me to have the space for my own vision: to gather the evidence and then build the story how I saw it. Although there is a need for some historical accuracy there is also freedom in being able to invent or infer the spaces Mary inhabited. There are many gaps in our knowledge about Mary too and this also allows for a joining up of the dots and perhaps as a woman myself, trying to think “well how would I feel?”.

Can you share a little about the projects you're currently working on and what we can look forward to reading from you in the future?

I am working on a new book about prehistoric cave painting loosely based on the book I made during my MA which should be out later this year. This is another narrative non-fiction book that aims to entice the reader into an underground world of storytelling, creativity and the human story. I am writing a musical that will bring my love of 3D and animation/puppetry to life, also revolving around the creative mind and the limitlessness of our imagination. I’m on a bit of a mission to remind everyone how important creativity is; how integral it is to our being; how vital it is for our children to create, imagine, dream and play.

Mary was a creative thinker - she dared to dream up something no one had ever thought of before. That’s what I want to do with my work, I want to show new ways of looking at things and I want to take the reader on a magical journey.

The Fossil Hunter is published by Puffin, 978-0241469897, £8.99 pbk.

An interview with the winner of the Klaus Flugge Prize 2024

Kate Winter and Mini Grey discuss the Klaus Flugge Prize 2024 and share thoughts on the process of making picture books.

The Klaus Flugge Prize is funded personally by Klaus Flugge and run independently of Andersen Press.

Website maintenance & Copyright © 2024 Andersen Press. All Rights Reserved. Privacy & Cookie Policy.