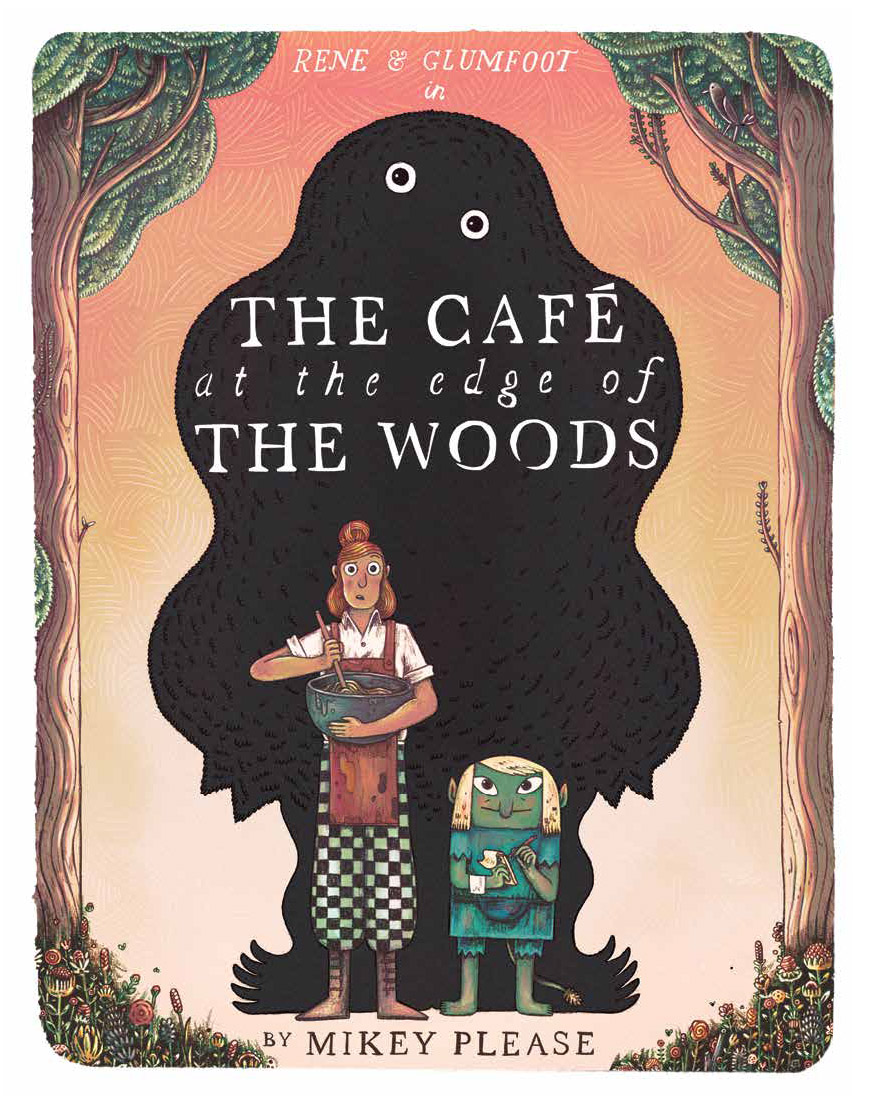

The Café at the Edge of the Woods, by Mikey Please

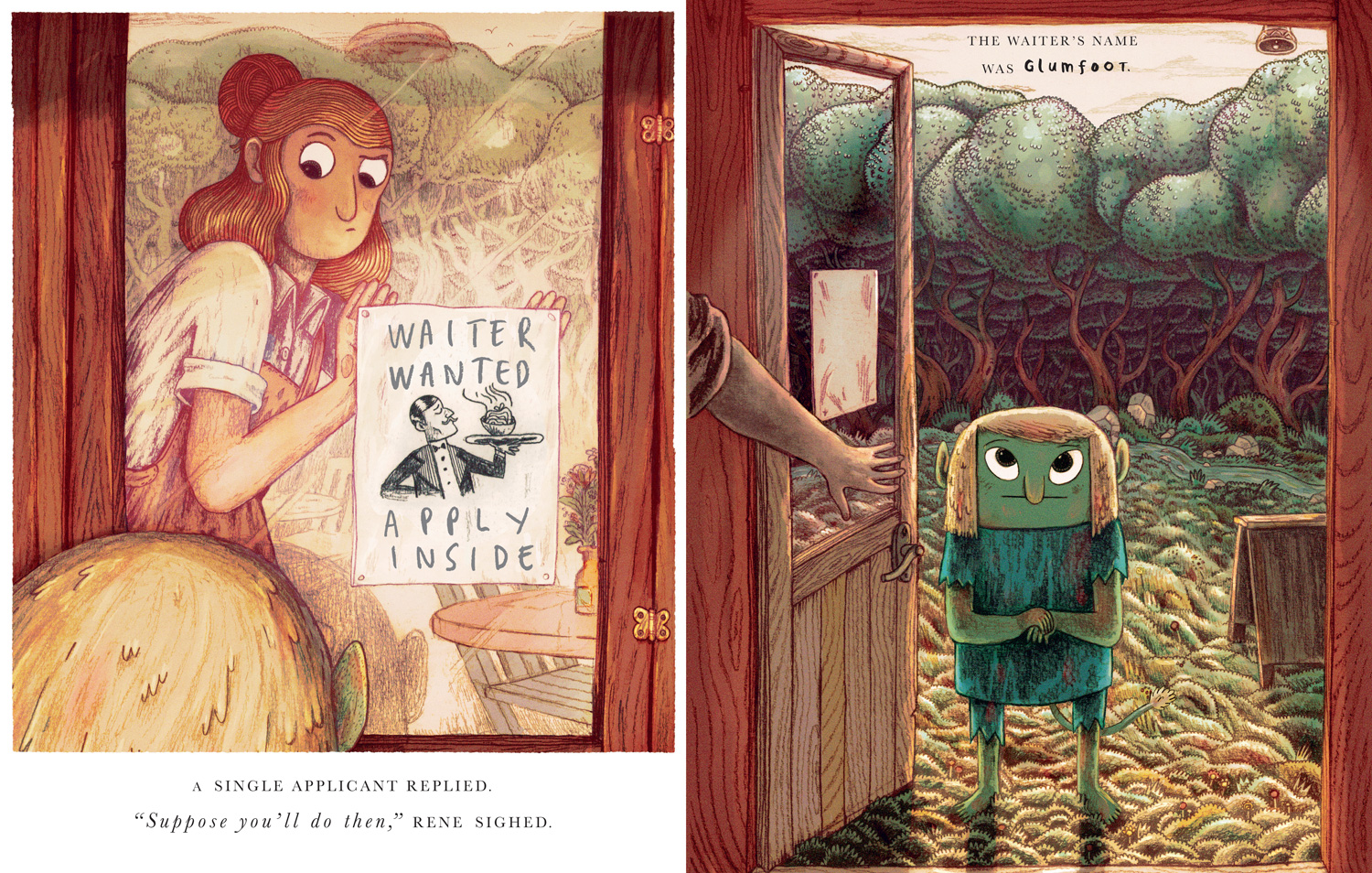

The Café at the Edge of the Woods is one of three books on the shortlist for the 2025 Klaus Flugge Prize. It stars Rene, whose dream of serving haute cuisine in her café at the edge of the woods seems doomed to failure when it fails to attract any customers. But then her resourceful waiter Glumfoot takes matters into his own hands and finds a whole new and enthusiastic clientele. The Waterstones Children’s Book Award was awarded to Mikey for the book and the Klaus Flugge Prize judges admire the tempo and the story structure. Not only is it a book to appeal to a wide range of readers, it will doubtless inspire future picture book makers too.

Former Klaus Flugge Prize judge, Senior Lecturer in Education: Primary English and Children's Literature, Oxford Brookes University, Mat Tobin interviewed Mikey about his book.

You’ve worked across many forms of visual storytelling - from award-winning animated films like The Eagleman Stag and Robin Robin, to storyboarding and model-making. What led you to explore the picturebook form with The Café at the Edge of the Woods? Did you find the process more like filmmaking… or more like something else entirely?

The picture book format felt like a very natural fit - nearly all of my narrative film projects have first been developed in book form before moving into animation. For instance, The Eagleman Stag began as a short, illustrated story, bound to resemble a lost diary. With Robin Robin, Dan Ojari and I created the story in a complete picture-book format long before adapting it into a screenplay. Partly, this was because we kept being told that - unless we changed our names to Julia Donaldson - there was no chance of getting a half-hour Christmas special commissioned in the UK. But primarily, it was because the picture book format allowed us to distill the story’s essence in a way that was both clear and digestible. The only unusual aspect of making Rene and Glumfoot was that I had to reveal what would normally remain a secret, embarrassing part of the development process - which meant, essentially, that I had to teach myself how to illustrate. There’s a beauty in the format of both picture books and short films, in that they must function within very limited real estate. There’s simply no room for excess or indulgence.

This book feels like it exists in a liminal space - both gentle and eerie, intimate and surreal. Were there particular visual references (e.g. forest folklore, Scandinavian design, old cartoons) or inspirations that helped shape this tone?

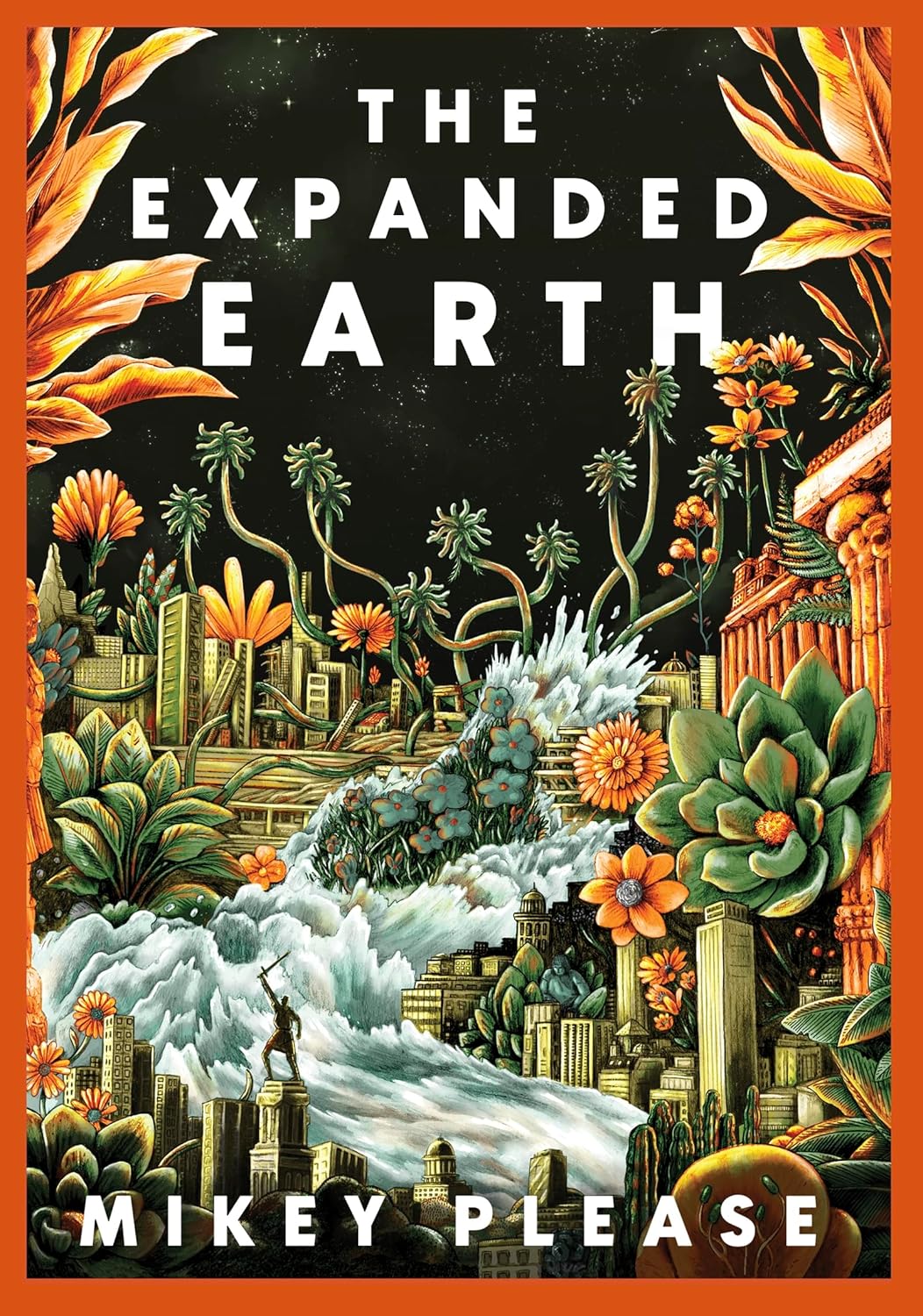

I’m not great with visual references and, dare I say, am even a little suspicious of them, worried they might unduly influence. I sketch as a way of research, but I try to avoid hunting for external references unless absolutely necessary. The big exception was The Expanded Earth, for which I gathered hundreds - if not thousands - of reference images, and even spent years photographing the world from a low vantage point to help work out the illustrations. But then the style in that set of illustrations was a lot more anchored in the real world. Otherwise, yes, I try to avoid things like mood boards.

I’m generally very time-poor (aren’t we all!), with two young kids and aging relatives, so when I sit down to work, I try to spend as little time as possible orbiting around producing actual content. When influences do creep in, it’s usually because they’ve entered my life organically. The bell above the café door, for instance, was something I discovered under sheets of ivy while replacing a garden fence. The Ogre’s hand, I realised, was influenced by a peculiar glove I picked up ten years ago at a jumble sale.

Let’s talk about perspective, and where the reader is placed within a scene. One of my favourite examples is the double-page spread where Glumfoot rolls out the food trolley to the towering customer. It feels so cinematic, almost like a tracking shot. How consciously do you think about the reader’s point of view when illustrating a scene? Are there techniques you’ve borrowed from animation or filmmaking that shape how you frame these moments — especially when playing with size and distance?

Storyboarding—the backbone of animation—has been an essential crossover skill, and I thoroughly recommend that both budding and seasoned picture-book makers take a course in it, if they can. There are countless rules, tricks, and techniques that help emphasise what’s important in a story through framing, lens choices, and lighting, etc. These are things I’ve considered constantly in my filmmaking work, and they apply just as well to picture books. For example, in the double-spread you mention, where Glumfoot feels the nervousness of betraying Rene, I tried to render his slightly queasy guilt feeling through the distortion you get with a the bulge of a fisheye lens.

While storyboarding is a hugely useful animation skill, I also learnt picture-book making has its own unique craft set: the format of the page, the drama of the page-turn, the challenge of conveying a wealth of information in a single image. Many of my usual filmmaking techniques didn’t carry over at all. I was so worried about embarrassing myself by getting the perspective in that particular spread wrong, that I built a 3D pre-vis model of the café interior - something I often do in animation - as a guide. But when I relied on the reference, the perfection drained the illustration of its energy. It lost its spark and personality! In the end, I scrapped both the pre-vis and the polished drawings, and embraced my own slightly wonky, broken perspective—which turned out to be far more fun.

The book’s portrait format feels more than a layout choice; it reflects the emotional shape of the story. The towering presence of the guest plays beautifully into this. Was that format decided early on? Did it grow out of Glumfoot and Rene’s journey — perhaps more internal than external — or from practical design conversations with Candice Turvey and Alice Blacker?

To be honest, I never really considered any other format. What can I say - I love portrait. I’m not sure I’ll ever make a landscape book, and if I did, it would have to be for a very good story-related reason. When I first mocked up The Café at the Edge of the Woods, it was already in portrait. I believe Candice and Alice suggested extending the height slightly from my original version, but that’s it. Sorry, not the most exciting answer!

I’m fascinated by Glumfoot — there’s something both archetypal and elusive about him. He feels a little like a Sancho Panza figure: grounded, dutiful, quietly wise… and just strange enough to be unforgettable. Did his design go through many changes? Was he always the calm, unassuming guide he seems to be now - or did he evolve significantly as the story took shape?

Yes, I too love Glumfoot. Sancho Panza is an excellent comparison! I wish I still had the office paper scraps where I first explored his design. From the beginning, I knew I wanted him to have a bold silhouette - an almost primary shape - dotted with little details, as a contrast to Rene’s more nebulous human design. He was always a goblin, and his name existed for a good six months before I tried to draw him, so by the time I did, he already felt familiar. This is the earliest drawing I can find - his hair is a little different, a little older-looking, but he’s almost entirely there.

Although he’s loosely based on my son - the story grew out of a game we played - Glumfoot quickly became his own entity. The Glumfoot of the story is (I’m pleased to say) a little more nervous and downtrodden than my son. There’s even a touch of Fawlty Towers’ Manuel in him. For the story, that felt right: Glumfoot is someone out of place in the human world, desperate to make things right, but at the same time terrified of getting everything wrong. By now, I’ve written a lot more of Glumfoot beyond The Café at the Edge of the Woods, and it’s been a joy watching him evolve, discovering that he is, in fact, a lot more mischievous than he first appears.

Rene is full of creative energy — ambitious, expressive, and driven to share her talents. But it takes Glumfoot’s quiet direction to help her truly understand her audience. Were you exploring something deeper here about the creative process — about the gap between intention and reception, or the value of those who see and support us before others do? Are there any parallels with your own creative journey?

Absolutely. I can’t help but draw on personal experience when it comes to hoping, dreaming, struggling, failing, collaborating, and compromising to make something work - all the things Rene herself goes through. But I was careful not to let any single ‘message’ dominate what I always wanted to be, first and foremost, a fun story for kids and parents to enjoy together.

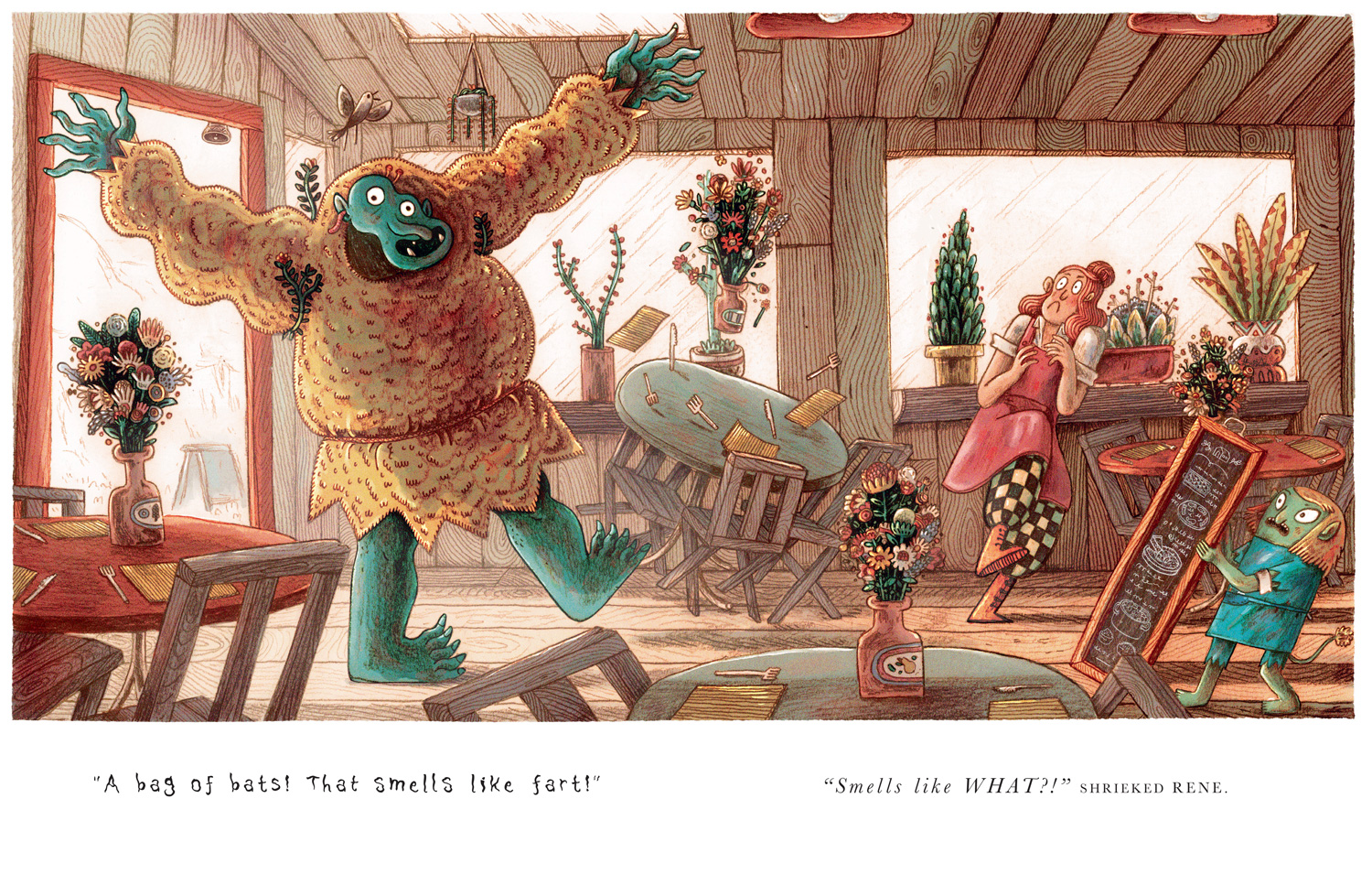

While there are certainly things I’d like to say, ideas I’d like to get across, I think the story works because Rene’s character grew out of what was needed to serve the story – a chef who rearranges her food into funny shapes to please her customers. What makes it compelling, though, is that Rene’s emotions are fully explored and change almost from page to page. From aspiration to weariness, satisfaction to hope, despair to delight, fear to outrage, passionate determination to nervousness - each turn reveals a new dimension of her character.

It makes her feel three-dimensional, and carries the reader along.

In my first draft, I had several other customers—witches, unicorns, and so on—but I cut them all to make space for Rene’s reactions. The biggest laugh usually doesn’t come from the Ogre demanding food that ‘smells like fart,’ but from Rene’s outrage at such an insulting request.

In animation, you often work with teams — directors, art leads, texture artists. In a book like this, how did your collaboration with the publisher, editor (Alice Blacker), and Art Director (Candice Turvey) unfold? Did they offer structure, freedom, or both?

It’s a very different working process! I’ve loved the directness of the author–publisher relationship, and without sounding too sycophantic, making The Café at the Edge of the Woods has been an utter delight. Of course, there’s still a large team involved in bringing the book to life - dozens of brilliant people - but the core creative process comes down, pretty much, to three of us: Alice, Candice, and myself. We have candid conversations, exchange critiques, shuffle pieces around, but luckily it always feels like we’re pulling in the same direction - to create a story that’s beautiful, clear, and entertaining.

Animation can be far more complex to navigate. Creative opinions come from every angle—clients, executives, compliance managers, producers, script editors—everyone has their say. I recently received a document that collated eight separate sets of notes on an eight-page script! It takes a great deal of diplomacy, and no small amount of careful treading, to steer any kind of vision through that kind of web.

The title Rene & Glumfoot in The Café at the Edge of the Woods suggests that this might not be their only adventure. Are there more stories planned for these two? Might we get to follow them again — or even discover where they came from?

I’m delighted to share that we have a confirmed series of no less than five Rene and Glumfoot books! Two more picture books and two middle grade novels. The second picture book, The Cave Downwind of the Café, is out September 11 2025, and the rest will follow yearly. And, yes, as if you knew, The Cave… will tell us a more about what’s on the other side of that looming wall of trees…

The Café at the Edge of the Woods is published by HarperCollins Children’s Books, 978-0008639013, £7.99 pbk

The Klaus Flugge Prize is funded personally by Klaus Flugge and run independently of Andersen Press.

Website maintenance & Copyright © 2024 Andersen Press. All Rights Reserved. Privacy & Cookie Policy.